You ask your doctor to make a diagnosis. You ask your teacher for a lesson. You ask your MP to give you the facts. You ask your mechanic to fix your car. What do these things have in common? You expect them to behave in your best interest.

In the corporate world, the same expectation has underpinned the capitalist system for centuries. But it presents a problem: the principal-agent problem. Here’s how it goes:

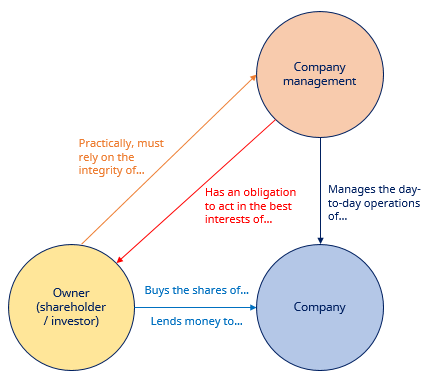

Owners (shareholders) of a business are not necessarily the managers of the business, and vice versa. The owners must therefore rely on the company management to act in a way that is good for the owners. In fact, the managers are obliged to do so.

It applies to governments, too, whereby the investors are known as ‘voters’. Governments should, it goes without saying, act in the best interest of their denizens at all times, just as company management should always act in the best interests of the company’s investors.

The cynics among us would say that it barely works. They’d say that the investor (the principal) and the manager (the agent) have conflicting interests, differing levels of information and unenforceable accountability. Humans just don’t work that way.

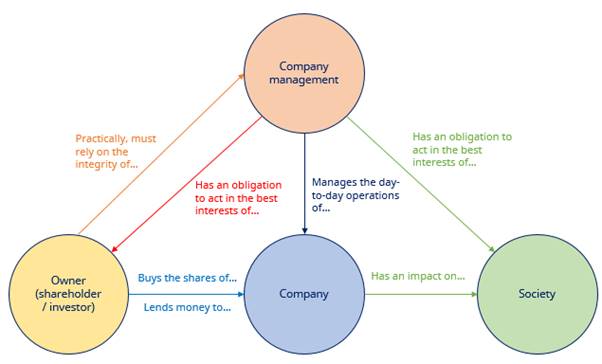

But whether it works or not, the definition of the problem is incomplete. There’s a third party in this relationship: society. The actions that corporations and governments take have knock-on effects to society, including the effects on the planet that society lives on.

Our definition of the principal-agent problem, therefore, is somewhat broader. Corporations and governments are obliged not merely to act in the best interests of their shareholders and voters, but of society as a whole.

The first chart represents what we now call ‘shareholder capitalism’, while the second chart represents a broader and more inclusive form of capitalism, known as ‘stakeholder capitalism’.

So, as agents that invest on behalf of asset owners (the principals), investment management companies, brokers, wealth managers and financial advisors should consider the impact that companies and countries have on society at large. To do that, they should assess the integrity of company management and of governmental institutions in their roles as agents in the capitalist system, and they should take every opportunity to hold them to account. The integration of this new dimension to formal investment processes is what has come to be known as sustainable investing.

We refer to lots of linked posts in this post. We hope that by following the links you can answer any questions you might have, but if anything is unclear in this post, or you have any questions relating to anything investment-related, please submit comments or questions in the section below and we’ll do our best to answer them.

Thanks for reading. Sign up to receive some or all of our new posts by registering your email address